India's Looming Debt Trap (Genre: Indian Economy)

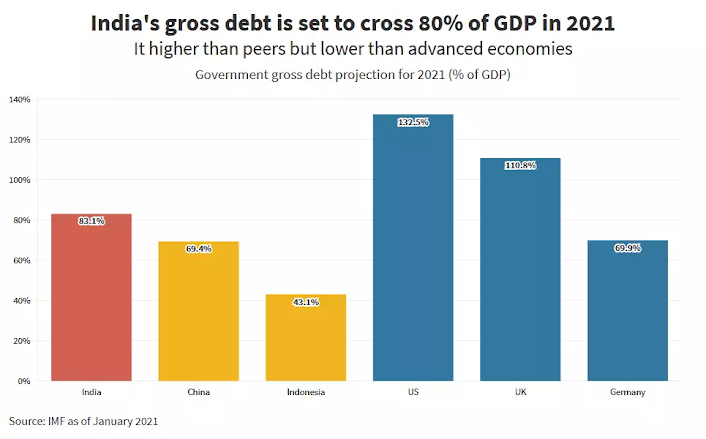

Since 1978-79, the Centre has been regularly running revenue deficits. The states too have been imitating the Centre from 1987-88. The result is that the combined outstanding liabilities of the Centre and states, net of loans advanced by the Centre to the states, total about 76% of GDP. This suffers in comparison with the figure of 62% for 1990-91, itself a year of financial turbulence for the country. This is a devastatingly horrific state of affairs!

A worse picture emerges if one looks at the ratio of total outstanding liabilities to total tax receipts. Between 1990-91 and 2002-3, this ratio deteriorated from 5.5 to 6.4 for the Centre. For the states, it worsened from 3.7 to 4.5.

Combined, for the Centre and the states, it slipped from 4 to 5. In other words, if all tax revenues of the Centre and the states were used only to pay back outstanding liabilities, neglecting interest on these liabilities and other claims such as defence or administrative expenditure, it would still take five years to discharge those liabilities!

As can be expected the Official apathy to the recent downgrade of Indian Rupee Debt suggests that Indians should not put off until tomorrow what they have to ask themselves today-how can they avoid a debt trap?

Cutting down on wasteful expenditure, improving the efficacy of revenue and capital outlays and broadening and deepening tax revenues is one approach. Tax revenues constitute 79% of combined revenue receipts of the Centre and the states. Of the tax revenues, 70% is derived from consumption taxes-customs, excise and sales taxes. When a large number of citizens have not only unsatisfied wants but also unfulfilled needs, there is a strong case for reduction of the incidence of these taxes.

The opportunity to increase tax revenues lies in reducing rates of the consumption taxes and stimulating volume growth, broadening the base for service tax and direct taxes, and improving efficiency in collection of taxes.

The other approach is to grow faster. The Tenth Plan document outlines a promising strategy for this purpose-tax reforms; fiscal prudence in the states and the Centre (including the downsizing of governments, and cuts in administrative overheads and subsidies); disinvestment; power reforms; labour reforms; and increasing foreign direct investment.

The states’ administrative machinery are bloated, their social sector and capital expenditure are wasteful. Not enough is done at the state level to improve the climate for economic growth, promote improvement in infrastructure or enhance the quality of life of their residents.

Over 75% of their revenue receipts are spent on non-development revenue expenditure and on interest. The states are shirking from levying a broad-based agricultural income tax, over-exploiting the sales tax and relying on conventional loans from the Centre and on market borrowing to finance their fiscal deficits.

Easy availability of funding spoils the states. All funding to the states, whether through the recommendations of the Finance Commissions or through central loans and grants or through market borrowings (over which the monetary authorities have some influence), must be ruthlessly linked to the implementation of the Tenth Plan strategies.

The Ministry of Finance, before releasing its loans and grants, and the Reserve Bank of India, prior to permitting market borrowings, must actively monitor states’ performance in this regard. The Reserve Bank can also force errant states to conform by discouraging banks from investing in securities of those states.

hi.... nice to see this blog

ReplyDeleteThanks dear.

Delete